What happened that made TypeScript viable for me and worth migrating paypal-scripts for.

Note: There was a lot of misunderstanding about this post so I want to make it clear that most of PayPal still uses JavaScript and this post is just to announce that PayPal engineers can now very easily choose between TypeScript and JavaScript for their projects without fiddling around with tooling.

NOTE: This is a cross-post from my newsletter. I publish each email two weeks after it’s sent. Subscribe to get more content like this earlier right in your inbox! 💌

Kent C. Dodds on Twitter

I've been using TypeScript for ~1 week now. Migrating from Flow. Breath. Of. Fresh. Air. I'll blog about this in a week or two. This is really great though.

At PayPal, I work on a tool called paypal-scripts which is a toolkit (like react-scripts from create-react-app, or angular-cli, or ember-cli or … etc…). I’ve written about it before. The idea is that it encapsulates all the tools common to PayPal applications and published modules. The goal being taking the huge list of devDependencies in the package.json and all the config files and reducing that down to one entry in the devDependencies. And because all the config lives within a single opinionated package, keeping things updated is a matter of updating one dependency (paypal-scripts) which typically does not need to make breaking changes. So you just keep that one dep updated and you go back to building your app.

For the last year, people at PayPal have opted-into adopting paypal-scripts. At PayPal, you create a new app by clicking a few buttons in a web UI which will create your GitHub (enterprise) repo and setup CI, deploys etc. etc. The GitHub repo it creates for you is based on a repo called the “sample-app.” Just last week, my PR to update it to use paypal-scripts was merged. This means that every new applications at PayPal will get their start with modern technology and tools that they don’t have to worry about keeping up to date. They will also be statically typed with TypeScript and tested with Jest.

Honestly, this is my Magnum Opus of my career. I honestly don’t think I’ll be able to top this at PayPal. The impact of this project is huge and I’m so grateful to PayPal for giving me the opportunity to work on something so huge.

/you shakes me awake

Right ok, back to the TypeScript thing.

So halfway through December, I was working on getting the sample-app updated to use paypal-scripts. I was also working on pp-react which is a (WIP) reusable component library for PayPal projects (buttons, modals, typography, etc.). Because paypal-scripts supports publishable modules, I was using paypal-scripts to build pp-react. A month ago, paypal-scripts shipped with support for FlowType. Support for FlowType was really easy to add to paypal-scripts thanks to Babel.

On December 12th, as I was working on Flow for both pp-react and the new sample-app, I finally got fed up with Flow (more on this later) and made a snap decision. I sent this to my co-worker Jamund Ferguson:

What would you say if I tried to make the sample app use TypeScript

To which he responded with:

YES DO IT

And so I took a poll of the #paypal-scripts slack channel and 100% of respondents said they wanted the change. That was good enough for me and I started the work on it. About a week later, I had totally migrated paypal-scripts from supporting Flow to supporting TypeScript (most of that time was making all the tools recognize .ts and .tsx files 🙄 and allowing paypal-scripts to dogfood itself which is kinda tricky 🐶). Then a few days of updating my sample-app PR to use the new and improved paypal-scripts and move from .js to .tsx and .ts files. Then we had Christmas break 🎄 and the week we got back after the new year 🎆, it was merged and now every new project starts off with modern tools that will stay updated by default and will be statically typed with TypeScript.

NOTE: Of course once people create their app, they are free to do whatever they like with it, they can remove all the code and switch to Elm or whatever and that’s totally fine. But most projects will stick with what they’re given thanks to the default effect.

What took took me so long?

Alright, so this is a question I get a lot from TypeScript fans. My head’s not been in the dirt. I remember evaluating TypeScript in ~2013 when a co-worker tried to convince us to adopt it in our 500k line codebase (he failed, but TS was pretty young at the time so I’m not too sad about it). I even interviewed Anders Hejlsberg (TypeScript creator) on JavaScript Air 2 years ago.

Here are the things that held me back from TypeScript:

Abandoning my existing toolchain of Babel and ESLint

This was definitely the biggest plus for Flow over TypeScript for me for many years. I’ve been using these tools for years and really enjoy building custom plugins for both Babel and ESLint (and you can too!). I love the huge community around both of these tools as well and I don’t want to give them up. Up until recently, I would have had to give them up if I wanted to use TypeScript. Sure there’s TSLint, but ESLint’s community is WAY bigger.

One thing I like about Flow is that all I need to do to adopt it is:

- Add the babel preset for the syntax

- Add // @flow to the top of every file I want to typecheck (there’s an eslint plugin to make sure you do)

- Add a script to run flow on the codebase to do typechecking

I really like that typechecking (via Flow) and code building (via babel, webpack, or rollup) are separate. I didn’t want to hand my life over to TypeScript, particularly if it wouldn’t understand my custom babel plugins anyway. Particularly because I had flow which was “good enough” (read more about this below).

From there, everything continues to work like normal. Well, thanks to Babel 7 (and more specifically @babel/preset-typescript), we can keep our tools and get most of TypeScript as well. The biggest trick is making tools accept the .ts and .tsx extensions, but thankfully that’s a solvable problem.

Forcing contributors to have to know TypeScript to contribute

I’m mostly talking about open source stuff, but this applies to work stuff as well. Though I always felt like work stuff should be typed and we were covered by Flow, I held myself back from adding it to my open source stuff for this reason. It’s one argument that I always told myself, but in the back of my mind I always had a rebuttal to myself: “Types are basically another form of testing which people have to learn to contribute as well. So they’re going to have to know or learn it to contribute anyway.”

It’s a pretty poor argument honestly and with more and more people learning TypeScript I think I’ll probably be authoring my open source packages in TypeScript in the future.

Flow Type Inference

I read and loved this blog post from Jamie Kyle. Especially the last line here:

With Flow you’ll be adding types to make errors nicer, not to uncover them.

This is absolutely true. Today, Flow has better type inference than TypeScript and that comforted me.

Flow is from Facebook just like React

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t succumb to this all-too common mistake of assuming that because a company was pushing one technology that I think is a real winner the other technologies must automatically be the best too. That’s not a given. That’s all I’ll say about this…

TypeScript Zealots 😬

Ok, so I think we can agree that when people are really excited about a technology they can’t stop telling people about it. Anyone here use vim? My experience is that TypeScript is no exception. The TypeScript community is full of wonderful people who are super kind, helpful, enthusiastic, and friendly.

But I’ve had interactions with people who would call you crazy or stupid for not using or understanding TypeScript or using anything else. That attitude is free of empathy and pretty snobbish. That is not the kind of community of which I want to be a part. I mean, it’s great to be enthusiastic about your technology choice, but it can go too far when you start insulting other people who have made different choices.

Kent C. Dodds on Twitter

Your impassioned love of TypeScript is sorta freaking me out.

This is still a concern that I have. Hopefully we can work together to improve the empathy of the community.

What was so wrong with Flow?

Ok, so as I said, I was fed up with Flow. Here’s one tweet that sums up my biggest issue with flow:

Kent C. Dodds on Twitter

Am I the only one that has a script called "fflow" that runs: "flow stop && flow" Pretty regularly if I run `flow` by itself it'll fail, but if I stop flow, then run it again it'll magically work... Am I alone in this?

Kent C. Dodds on Twitter

I love your enthusiasm @flowtype, but these look like errors to me 🤔

The regular unreliability of flow was what finally made me give up on it. The editor plugins only sometimes worked (full disclosure, I never tried Nuclide and maybe my life would’ve been different if I had, but I tried flow in Atom and VSCode) and I would get issues like the one all the time. It was incredibly frustrating because I could never trust my type checker. There were other issues as well.

When I saw this tweet thread from Jamie Kyle back in November, it really resonated with me and my experience. I honestly couldn’t stop thinking that I should really give TypeScript a solid shake. So I finally did and I’m glad that I did!

Other questions and answers…

Why not TSLint?

I actually implemented TSLint in paypal-scripts. It was one of the first scripts that I got working. I would detect whether to use TSLint or ESLint based on whether your project had a tsconfig.json file. But then I remembered that we actually have some custom ESLint plugins (for example, some for internationalization) that I didn’t want to spend time rewriting as TSLint plugins. Also, the TSLint CLI is not quite as capable as ESLint and it didn’t really work nicely for the way that paypal-scripts work. I may investigate TSLint again in the future. Oh, and the ESLint community is still WAY bigger. I’ve also been slowly been discovering that a reliable typechecker makes linting plugins useless. But for now using ESLint with TypeScript is not bad at all. And check it out, I show you how to do it in this DevTip.

Oh, and it looks like the TypeScript team is investing in ESLint over TSLint so I guess I’m making the right bet :)

Why not Reason?

In the tweet referenced above, my co-worker Jamund tweeted:

It may be time to try @typescriptlang!!!

To which I responded:

Honestly, if I’m going to make a change, it’ll be @reasonml :P

I’ve often said that I’d switch to Reason before switching to TypeScript. A big reason for this was what I mentioned above about having to abandon my existing tools. But because I wasn’t forced to face that, TypeScript was more attractive. I’m still excited by Reason, but switching to Reason would have been a HUGE jump for lots of people at PayPal and while I think they’re super smart and capable people, I think they’ll be more productive using TypeScript than trying to learn a new language.

What would have happened if I’d gone with Reason is I’d probably never have gotten my PR merged into the sample-app. It’s one thing to get buy-in from folks about using something that’s basically JavaScript with types (especially when there’s basically no config to maintain), but it’s an entirely different conversation to convince them to use an entirely different language and ecosystem (no matter how good that language’s inter-op with npm/JS is).

Thanks

Kent C. Dodds on Twitter

I want to say thank you to all you people on Twitter who have helped me learn a bunch about TypeScript these last few weeks. You've been super and I hope to pay it forward in the form of learning materials for the next wave of TypeScript learners. Thanks!

Seriously, twitter people helped me a LOT as I was making the adjustment, so thank you! I am going to try to make stuff to help people learn TypeScript. Here’s one thing I made recently based on stuff I learned from twitter folks: TypeScript: Why you have to add types even if you handle the undefined case.

Conclusion

As I said, getting paypal-scripts into PayPal’s sample-app is probably the thing I’m most proud of from a career standpoint. It’s going to make a HUGE impact. The fact that I was able to slip in TypeScript support at the very end there is a HUGE win for PayPal employees. I’m really happy about the decision to adopt TypeScript.

👋 Hi! I’m Kent C. Dodds. I work at PayPal as a full stack JavaScript engineer. I represent PayPal on the TC39. I’m actively involved in the open source community. I’m the creator of TestingJavaScript.com and I’m an instructor on egghead.io and Frontend Masters. I’m also a Google Developer Expert. I’m happily married and the father of four kids. I like my family, code, JavaScript, and React.

A few questions and answers about testing in JavaScript

The Assert(js) Conference is just about a month away. I’m really excited about attending, speaking, and workshopping at a conference all about testing JavaScript.

In preparation for the conference, the organizers invited us speakers to answer a few questions about testing. Here are my answers!

What testing tools and/or workflow do you use?

I’ve used pretty much every testing tool for JavaScript there is. I started with QUnit, then used Jasmine, Mocha, sprinkled some Karma to run things, and then I had to figure out how to make things work with babel and webpack, then throwing in code coverage reporting made things really complicated. I even gave a meetup talk called “ES6, Webpack, Karma, and Code Coverage” because it was complicated enough to justify a 45 minute demo/tutorial.

To make a long story short, I eventually bumped into Jest: reborn. I’d used Jest when it was the joker testing framework (pun intended) because it was so slow, but I started to hear it was getting fast. Like… reeeally fast. On top of that, it had all the configuration baked-in. And it has the most incredible watch mode ever.

So, what tool do I use? I’m in love with Jest. ❤️🃏

That said, if I want to run E2E tests, I have to recommend Cypress. No more selenium for me. Cypress.io is where it’s at. Watch this for more on why.

What is one thing would you change in the JS testing ecosystem?

I think that we as a community are in love with poking holes in the world of our applications to make things easier to test by creating Test Doubles/mocks/stubs for anything and everything. Whether it’s shallow rendering a react component or mocking all of its dependencies, we’re reducing our confidence that our applications work properly by mocking the world and testing implementation details.

For more on this, I suggest checking out my blog post: “Write tests. Not too many. Mostly integration.”

Write tests. Not too many. Mostly integration.

A lot of people in the JS world don’t have a lot of experience in testing. How would you recommend they get started?

I think one of the things that makes testing hard is not understanding what’s going on with testing frameworks. That’s why I wrote the blog post “But really, what is a JavaScript test?”

But really, what is a JavaScript test?

In it I show what a test is, define a few terms, and help folks come to understand what a test is. Once you get that basic concept down, then everything else becomes much easier to understand and use.

P.S. If you like this, make sure to subscribe to my newsletter, follow me on twitter, buy me lunch, and share this with your friends 😀

Also, retweeting this is a great way to share this with your friends:

Kent C. Dodds on Twitter

I just published "Assert(js) Speaker Series: Thoughts on Testing" https://t.co/4D3dyML3bL

Assert(js) Speaker Series: thoughts on Testing was originally published in Assert(js) Testing Conf on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

]]>

The live broadcast podcast all about JavaScript

I’m pleased to announce JavaScript Air! This is a live video broadcast podcast all about JavaScript and the web and the first episode, “The past, present, and future of JavaScript,” will be with BrendanEich. I couldn’t be more stoked to have the original creator of JavaScript on for the first episode of this new show.

Add the event to your calendar by RSVPing to the Google+ event.

How it works

Shows will air live using Hangouts on Air. The show will air regularly on Wednesdays at 12:00 CST. They will be available on YouTube immediately after the show and later published to an audio podcast (available on iTunes). We’ll be talking about anything relating to the JavaScript and the web. Guest and topic suggestions welcome!

The People

The show is hosted by me (Kent C. Dodds) and is paneled by some of the coolest developers around (sorted alphabetically by twitter handle of course).

- Dan Abramov

- Brian Lonsdorf

- Kyle Simpson

- Iheanyi Ekechukwu

- Lin Clark

- Matt Zabriskie

- Pam Selle

- Tyler McGinnis

I’m super excited to have these fantastic people on the show with me and I look forward to all of the awesome content we can deliver for the community!

Sponsors

Egghead.io is the premier sponsor for the show. Several of the panelists (and me) have created content for Egghead. I recommend you go check it out and subscribe to them. They’re awesome! If you or your company is interested in sponsoring, please contact me: [email protected]

Follow/Subscribe

Follow and/or subscribe and prepare for some wickedly awesome content! Twitter, Google+, Facebook, YouTube, iTunes, RSS Feed

Brief History

A year ago Todd Motto and I started Angular Air. It’s been an awesome experience. I recently decided that I could do more for the community by focusing more on JavaScript. So I handed off management and ownership of Angular Air to Angular Class and hosting to Jeff Whelpley and I’ll be focusing my attention on JavaScript Air.

You can see the announcement in my last episode of Angular Air: “The Importance of Learning JavaScript” with Kyle (the whole episode was awesome, but if you just want to see the announcement, it was at the end).

Thanks!

I want to say thanks to everyone who’s supported me with Angular Air and encouraged me to keep this going. I’m looking forward to helping provide the community with high quality content to keep us all current and relevant in this exciting fast-paced industry! See you around!

One more thing

If you thought this was interesting, you might like to check out the rest of my blog and subscribe to my newsletter 💌 (newsletters are published to my blog 2 weeks after they’re emailed out).

UPDATE: I now try to avoid using testing lifecycle hooks or nesting describes at all. Listen to me talk about it for 3 minutes here. In fact, now that I’m using Jest (learn Jest), I don’t even use describe either. I find it’s much better this way. But if you want to use lifecycle hooks anyway, this blogpost is still relevant.

With mocha (and jasmine) you have a few hooks into the testing lifecycle: describe, before, after, beforeEach, afterEach, and it. What do these all mean? When do I use one over another? What do I put in each of these? I’m going to attempt to answer this to my best abilities according to my personal experience.

describe

Used to group tests about a unit or a component together. You can nest describe statements to be more specific about a piece of a unit. I nest these when I’m testing a module that has several methods I can call. For example:

import wand from './wand'

describe(`wand`, function() {

describe(`createUnicorn`, function() {

// test wand.createUnicorn

})

})In the context of E2E testing of a page, I’d group like-tests that require similar set-up/tear-down and/or specific parts or components of the page you’re testing. Honestly I have limited experience with this type of testing, but the general rule should be group things that can be described together.

before/after

This runs in the scope of the describe. As the names imply, they run before and after the set of contained tests and only run once each. This is handy if you need to set up or tear down state for all of the tests. These things should not need modification between tests. I generally favor beforeEach and afterEach to ensure that your state is reset between tests. But in E2E this might be a little expensive, so sharing that state between tests may not be a bad idea.

You can have multiple of each of these (they’re executed in the order they appear). I normally only have one, but it can be handy if you want to group and label set-up or tear-down. Generally, these should not contain any kind of assertions.

As far as placement, I would recommend you place them where you would cognitively think they should run:

import wand from './wand'

describe(`wand`, function() {

describe(`createUnicorn`, function() {

before(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// set up state before any of the tests run

})// test wand.createUnicorn

after(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// tear down state after all of the tests run

})

})

})beforeEach/afterEach

These run for every single individual test. So if you have 3 tests, these will each run 3 times. Use this only for stuff that’s shared across all of your statements. I often use this to set up some state that needs to exist (when the thing I’m testing isn’t stateless 😒) or to create convenience objects/functions that are not stateless.

You can have multiple of each of these (they’re executed in the order they appear). I normally only have one, but it can be handy if you want to group and label set-up or tear-down. Generally, these should not contain any kind of assertions.

import wand from './wand'

describe(`wand`, function() {

describe(`createUnicorn`, function() {

before(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// set up state before any of the tests run

}) beforeEach(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// set up state before each of the tests run

})// test wand.createUnicorn

afterEach(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// tear down state after each of the tests run

}) after(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// tear down state after all of the tests run

})

})

})it

This is where your actual assertions come in. If you do not have assertions in these, you’re doing it wrong. Each it statement should be totall isolated from any of the other it statements. Each should be able to run without any other test running.

For assertions, with Mocha, I recommend Chai and personally prefer the expect assertion style. Once you’ve set up the state you need for your test, you use that state to perform the actions to get the output you’ll be asserting.

The best test checks expected output with actual output

This is really easy to do when you’re testing something that’s stateless, but the reality is that many of us (particularly in the Angular community) have a really hard time writing components (especially directives) that are stateless. Hopefully by writing your tests before you implement will help encourage you to write stateless stuff because it’s just easier to test.

Anyway, as you would expect, your it statement will go between the beforeEach and afterEach:

import wand from './wand'

describe(`wand`, function() {

describe(`createUnicorn`, function() {

before(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// set up state before any of the tests run

}) beforeEach(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// set up state before each of the tests run

}) it(`should create me a new unicorn object`, function() {

const actual = wand.createUnicorn()

const expected = {name: 'Fred'}

expect(actual).to.deep.equal(expected)

}) afterEach(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// tear down state after each of the tests run

}) after(`optional descriptive message`, function() {

// tear down state after all of the tests run

})

})

})Conclusion

Again, I’m not some kind of amazing tester and some of these opinions may be a little off, but I feel like they’re pretty solid and it’s worked out pretty well for me and stuff I do.

I recommend you check out Eric Elliott’s 5 Questions Every Unit Test Must Answer post. Here are the questions:

- What are you testing?

- What should it do?

- What is the actual output?

- What is the expected output?

- How can the test be reproduced?

I try to adapt Eric’s recommendations to my Mocha tests. Eric also has a post on why he doesn’t use Mocha that I recommend you check out as well. Moving from Mocha to something like Tape pretty much removes all of this confusion.

I hope this helps clear up some of that confusion. If you have feedback or comments, please feel free to give them as a comment or response. I wrote this post because I couldn’t find anything quite like it. If you know of one, let me know!

QYMA

(Questions You Might Ask)

Q: Why are you using template literals for your strings!? A: This

I’m converting my project to use webpack for a ton of reasons. It’s awesome. This has given me the opportunity to reflect on the relationship between angular modules and npm modules and I think I’ve determined what I believe to be the best way for angular module developers to show the npm angular developers some love. (And, I encourage you to join the promised land)

Step 1

Create a dist directory where you place a file that ships everything you need to use the module (unminified). Then set your package.json’s “main” property to this file. This makes it so when I `require(‘your-library’)` it resolves to that file.

Step 2

Use UMD to wrap your module (definitely recommend doing this as part of your build). The angular-ui-router does this (CommonJS only, and still depends on angular being global, but still, it’s great). This is very important! Here’s a simple example of a module that gives you a directive “log-when-linked” that logs out when an element is linked.

Notice the example of what this allows me to do in the README. Make sure to return export the module name! It also makes it really easy for AMD users (if you’re still into that) and it’s not any different for global namespace users. It’s really a beautiful thing. (Check my echo library for an example of how to build to UMD with webpack).

Step 3

Publish to npm! Please! It’s very easy: https://gist.github.com/coolaj86/1318304

Step 4

Put it up on http://ngmodules.org/ because we want to know about it :-)

Step 5

Switch your project to webpack, and use ES6, because it’ll set you free :-)

Thanks! Let me know what you think as a comment or on Twitter. If you have suggestions on articles or build systems or other tools on making this easier for people to do, please feel free to link to them in a comment!

Note: All this UMD pain goes away when we’re all using ES6 modules :-) Start using ES6 now and that’ll be easier too!

Edit: This is the method that the Angular team will be following for all the angular modules (see PR).

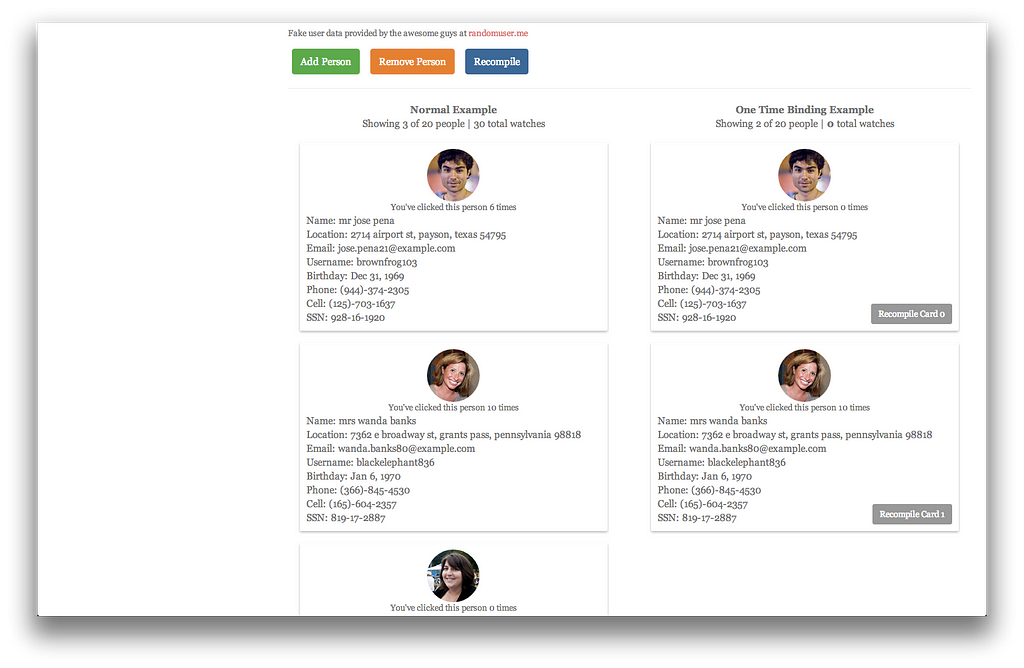

I was intrigued by the slides from Vjeux entitled “React: CSS in JS” (which is very good stuff and I would encourage you to read through it). I decided to see what it would look like to create something similar with Angular. turns out it’s not that bad and it’s actually kind of refreshing. I think I’ll keep looking into this…

Here’s a demo that I built when experimenting with the concept:

So there’s definitely room for additional abstractions here to make it easier to manage, but I can see some serious potential with this approach and will definitely investigate it further (perhaps even release a library with the necessary abstractions). It’s actually sort of delightful to write styles this way…

What are your thoughts on this? In my mind, I see ReactJS personified as a ninja with a sword called JavaScript and he’s whacking away at HTML and CSS (not as cool ninjas apparently) because he doesn’t need them anymore. Maybe that’s a little strong for what is actually going on, but I think the imagery is kind of cool.

For the non-trivial Angular Application

If you’ve worked on a sizeable AngularJS application, you’ll discover that while Angular’s digest cycle is awesome, it can also make your app seem sluggish as it grows and that digest cycle takes longer. So it becomes important to watch your watchers because even though one wont really cause an issue, the more you have, the worse it gets.

In an app I’m working on at work, we have areas of the app that can get a rather large watch count fast. Most pages sit at around 2,000, but some grow up to over 20,000 or 30,000! This can make the digest cycle take hundreds of milliseconds to complete resulting in a pretty janky experience for the users.

There’s Hope!

AngularJS version 1.3 will bring our expressions something called “One-time binding.” Basically, by adding two colons “::” to your expression, you tell Angular “hey, once this expression returns a value, stop watching it.” This can drastically reduce your watch count, particularly in an ng-repeat. And for those of you who can’t update just yet (1.3 is still in beta) you can take advantage of the bindonce module which attempts to do the same thing and does so decently well.

The Problem

So, let’s say you have something that does update, but does so infrequently and you know when it does (like a promise resolution or browser event). Well, you’re stuck watching anyway because Angular’s one-time binding wont listen for changes anymore. What you really need is a way to tell Angular to recompile the template…

A Solution! kcd-recompile

A directive that stores the template of its children and will recompile its children on demand. I’ve written just such a directive. It’s easy to use and it was a relatively small implementation

Usage:

Implementation:

This directive is one of several (and more to come) “Angular Things” that I’ve made (or found/modified) in my “kcd” module. Feel free to see the interactive demo site where you can play around with the demo and figure out how to use this directive: http://kentcdodds.com/kcd-angular/#/kcd-recompile

I’m really looking forward to when Angular 1.3 is officially released and we can update where I work. For now, I’m using the kcd-recompile directive with bindonce and it is working splendidly. Good luck! And may your digest cycles always be short :-)

Reduce AngularJS Watch Count…

What makes AngularJS more slow than anything else I’ve encountered is having a ton of watchers. For those of you who aren’t familiar with how AngularJS does its two-way databinding, essentially you tell Angular to watch something for changes, and Angular will check it over and over and over and over and over…. and over. Most of the time, the browser is fast enough that this is not a big issue, but many people have found that this can be a real issue as the app (and number of watchers) grows.

Angular adds a watcher to the digest cycle for each of these:

- {{expression}} — In your templates (and anywhere else where there’s an expression)

- $scope.$watch(‘expression/function’) — In your JavaScript

Count the Watchers

This simple script will help you identify watch heavy areas of your app:

Just paste that into your console (or use Chrome snippets) and use like so:

// get all watchers on the whole page

getWatchers();

// get watchers of a specific element (and its children)

getWatchers(document.body);

// select the element of interest in Chrome Dev tools

getWatchers($0);

It will return an array of watchers of the element you gave and all its children.

Surprised? Reduce your watch count…

Lucky for us, Angular 1.3 is shipping with one-time binding which will make it so we can reduce our watch count in the template. This will be super useful. Unfortunately, until you can update your version of Angular, you need to watch out for how many watches you have.

If you’re stuck on < Angular 1.3 then you do have an alternative solution with a module called bindonce that does a good job of reducing your watch count. You may want to take a look at this if you’re in this boat.

Angular’s digest cycle enables one of the best things about working with Angular, but it can come and bite you if you’re not thoughtful about it. Hopefully this helps you identify bottleneck areas of your app.

Browserify? Require.js? Concat w/ Sourcemaps? An alternative approach…

IMPORTANT NOTE: I now use webpack and, as awesome as this was, it has some serious shortcomings. My experience with webpack has been SO much better! I even made an egghead.io series on Angular and Webpack for Modular Applications.

I just read a medium post by @dickeyxxx about simplifying your Angular app’s script loading by simply leveraging Angular’s built-in module system and simply concatenating your source for dev and making source maps in favor over browserify or requirejs which can be more complicated. I’d like to suggest an alternative approach to accomplishing the same thing which I think may be even simpler.

The problem: Loading Scripts

What we’re really trying to accomplish here is two fold:

- Make sure all our files load in the right order

- Prevent the need for us to write script tags for every file by hand…

With the way Angular is currently. It pretty much takes care of #1 for us with its dependency injection and module system. (I’m pretty sure) that all you need to do is make sure that the module is created before you attempt to register anything on it (directives, services, controllers, etc.) and any of a module’s dependencies also need to be loaded. Other than that, it doesn’t really matter what order things load.

So, taking those constraints into consideration, we just need to make sure that the files we need are loaded into the browser while we’re developing. Putting in the scripts by hand is madness. All we really want is to say: “Hey browser, take all of the JavaScript files in this directory, and load them up will yah?” How many projects do you have where you aren’t loading every JavaScript file? Sure there are bower_components and other vendor files, but those are a separate animal. If you’re not loading all the files you are writing into the browser then what the heck is it doing in your repo?

As a side, at work, we use require to load all of our files. I know requirejs is more than just loading scripts, but please tell me how manually writing and maintaining this:

require('app.js');

require('main/MainCtrl');

require('github/GitHubService');

require('candy/FavoriteCandyService');

// go on forever...Is any less of a nightmare than manually writing this:

<script src="app.js"></script>

<script src="main/MainCtrl.js"></script>

<script src="github/GitHubService.js"></script>

<script src="candy/FavoriteCandyService.js"></script>

<!-- go on forever... -->

Our app is riddled with the former, and I don’t really see that being much better than the latter…

A Solution: Grunt (or gulp, or whatever) + Jade (or ejs or whatever)

In my naivety, I created my own little node program that adds a script tag to my index.html for all the files in my project’s folder. It works great and my output looks like a huge html file with a billion script tags in it, but I don’t care, because what I have to maintain is very small and it works like a charm.

If you want, here’s how I’m doing it in a side project. Some of it is dependant on how I’ve structured my project, so you may have some differences in how you implement it, but I’d recommend trying it out :-)

Here’s my index.jade:

and part of my Gruntfile.js

In the grunt config, you’ll notice a reference to “getIndexData.” This is the main magic of how things are automatically loaded. You’ll notice that vendor files (bower_components) are specifically added. Don’t know how you could get around that… But then I glob for everything using the constraints mentioned above. See it below:

I hope this is helpful for you. It’s certainly simpler for me to simply run “grunt jade” than worry about requiring stuff all over my code.

Compare/Contrast Million Scripts method with Concat & Sourcemap method

This is where I further convince you of my lack of knowledge…

The concat & Sourcemap method that @dickeyxxx recommends is awesome. I’d like to just write some of my thoughts to compare/contrast these two methods:

- They both accomplish the same task: Once you have it up and running, you don’t have to worry about writing/maintaining madness (require statements etc.)

- Concat & Sourcemap needs to run every time you change anything. I’m not certain how long that takes, but if it takes much time, then you’re stuck waiting for that task to run before you refresh your browser, which could be annoying. Especially if you’re compiling from CoffeeScript or TypeScript already. But, this may be such a negligible amount of time that this is simply a difference, neither good nor bad. Million Scripts only needs to run when you add/remove a file.

- Million Scripts requires the browser to load a ton of scripts every time you refresh whereas Concat & Sourcemap only needs the loading of one file (+ the sourcemap). Each of these is good and bad. I believe the browser only loads 6 files at once, so it may take a second longer to load the Million Scripts method. However, locally (where you should be doing this) that’s probably a non-issue. With Concat & Sourcemap, the browser has to split the parse the sourcemap and split it up. If you have a few vendor files in there, this may take a second too…

Conclusion

Hurray for multiple solutions to the same problem! I hope there’s always more than one way to do complex things because it makes it possible for you to evaluate the solutions and pick the one that works best for your situation.

Disclaimer: The largest codebase I’ve tried this on is about 5,000 lines of Angular JavaScript. Not sure how it scales… But I expect it would scale about as well as anything else…

Another Note: This is obviously just for development purposes. When you’re going to production, you’re going to want to concat and minify your source, yada yada yada. Loading 100 js files in the browser is not the best idea in the world…